By Christina Hoag

In 1976, we left Australia for America. It was my seventh international move, my father’s eighth, my mother’s ninth. It was the move that fractured my family forever.

Dad was to be president of the US subsidiary of the Swedish industrial multinational he worked for. He’d held an equivalent position with the company in Australia, but the United States was a much larger market. For him, it was a big promotion. For us, my mother and we three kids, it was yet another uprooting. It came just five years after his assurance that Sydney was the place we would finally call home.

The cracks in our family appeared soon after our arrival in New Jersey. That year my sister, brother and I attended a total of three schools, plus a summer day camp where at thirteen, I was the oldest kid in the entire place.

None of us was prepared for American life.

Stress for my mother, particularly about driving on the other side of the road and on highways she’d never seen so jampacked, caused her to break out in shingles. And she was alone. My father absented himself on business trip after business trip. I recall going on two strained family outings that summer: to see Franklin Roosevelt’s home at Hyde Park, which meant little to us as kids but which Dad wanted to see, and a Circle Line boat tour of Manhattan. For our first Thanksgiving we had spaghetti and tried to stay warm as a Northern Hemisphere winter approached.

None of us was prepared for American life. While Dad delighted in the custom of holding business meetings over breakfast, he wasn’t prepared for the rapacious competitiveness of the US market. The work culture was different, too. It lacked the bonhomie of Australia’s relaxed, egalitarian culture. In Sydney, we often socialized as a family with my father’s colleagues, going to beach picnics and barbecues. My parents went out a lot to fancy dinners and operas and cocktail parties. Mum had a wardrobe of evening gowns and accessories.

They also entertained a lot at home, which was exciting for us kids. We’d watch from the top of the stairs as dinner guests arrived at the front door. For parties, we’d be enlisted to refill peanut bowls. Every year, my parents hosted a bash for the managers and their spouses, and two Christmas drinks get-togethers, one for neighbors and non-work friends and another for company people. A particularly memorable affair was a blowout for my dad’s fortieth birthday. I woke up to loud music and crept downstairs to see a conga line shimmying around the living room at two in the morning.

Dad tried to replicate that cohesive atmosphere in New Jersey, but it didn’t work. A managers’ evening flopped when the guests were stiff and uptight in front of the boss. The same with smaller dinner parties. The events were never repeated. The company didn’t even hold a Christmas event that included families. Mum’s evening gowns gathered dust in the closet.

My father was a daily drinker throughout his life, but it worsened in America. The doorbell rang one night. I opened the door to see Dad flanked by two men holding him upright. “Get your mother,” he managed to spit out as he lurched forward. I ran off. Nothing more was said about that. Another morning, I left for school and noticed the mailbox had mysteriously taken on a sharp lean overnight. “Somebody must’ve clipped it as they drove along the road,” my father said later. Sure, Dad.

We were all affected. My brother was bullied at school and started to overeat. His weight ballooned. My sister and I had to fit into American teenage culture where kids grew up ultra- fast—cigarettes, pot, rock music, and boyfriends were badges of acceptance. My sister ran with a rough crowd, while I papered my room with posters of the Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin, puffed on Marlboro Lights, and counted the days until I could leave for university.

My parents had no idea what to do with American teenagers except cling to the archaic British tradition of packing kids off to boarding school. A year after our arrival, they sent away for a brochure for a girls’ school in Central New Jersey for me, but I refused to go, galled at the thought of yet another move. We’d just arrived in a new country. My family was all I had. Now I was supposed to be entirely on my own?

As time went on, we evolved into a bunch of people siloed in the same house. Some of that disconnection was undoubtedly due to the normal adolescent desire for individuality, but as a therapist pointed out to me years later, much of it was because we were each focused on trying to survive in our new environment. My siblings and I rarely spoke. Dad was constantly away. When he was home, he holed up in the living room, drinking wine, cutting his toenails, and reading financial news to loud classical music that discouraged conversation. He refused to attend my brother’s soccer games with the excuse that his father hadn’t attended his rugby matches. My mother kept the household going in the background.

Then, three and a half years after we arrived, our lives turned overnight into a never-ending soap opera. My mother discovered photos in Dad’s briefcase one night. I happened to come upon her as she held the pictures in her hand, shock registering on her face. I tried to think of excuses for why Dad would have photos of a young blond woman with a small child on her lap in his briefcase. He’d probably brought the photos back from Stockholm for a colleague, I said. Mum knew the truth, of course, which was why she was rifling through his briefcase in the first place. He was having an affair. The child in the photos wasn’t his, Dad said. That, at least, proved to be true. He was forty-five. She was twenty-eight. I was sixteen. It was such a cliché, it was embarrassing. What came next, I thought, the stereotypical Porsche roadster? It was worse. Over the next three years, my parents divorced. My father got fired. He had two children by different women in the same year. He made disastrous investments. He took to buying flagons of cheap red wine and was smashed whenever I saw him. And we got stuck in a country where no one but he had wanted to come. My mother considered taking us to England, but at the time no one had the stomach for another international move. We morphed from expats into immigrants.

I became ashamed of my broken family. None of my friends had divorced parents. It was another mark of difference on top of my accent, my international upbringing. Another hurdle I had to work to overcome. The cracks in my family deepened into fissures of unresolved grief and anger and resentment that only worsened with time. We lived scattershot all over the United States. My brother estranged himself from the rest of the family. My sister and I had perfunctory relationships with our father. She had a little more with our mother. I had a closer relationship.

Around the year 2000, Dad decided to spend half the year in New Zealand. I asked him for his address. “Just contact me through the office,” he said. My mother uttered an eerily similar statement around the same time: “It would be too close if we lived in the same city.” After decades of living away from their own families, they just didn’t know how to have a family with grown children.

Shortly before Dad died from an alcoholism-related cancer in 2009, we all gathered around his hospital bed, his first and second families. I hadn’t seen my half-brother in thirty years and had never met my nephew, my brother’s son. At that point, I didn’t even know I had another half-sister. That came later, thanks to genealogical DNA testing. Amid the hustle-bustle, I managed a few minutes alone with my father. I wanted him to utter some words of contriteness, to acknowledge that the last move was one move too many.

He never did.

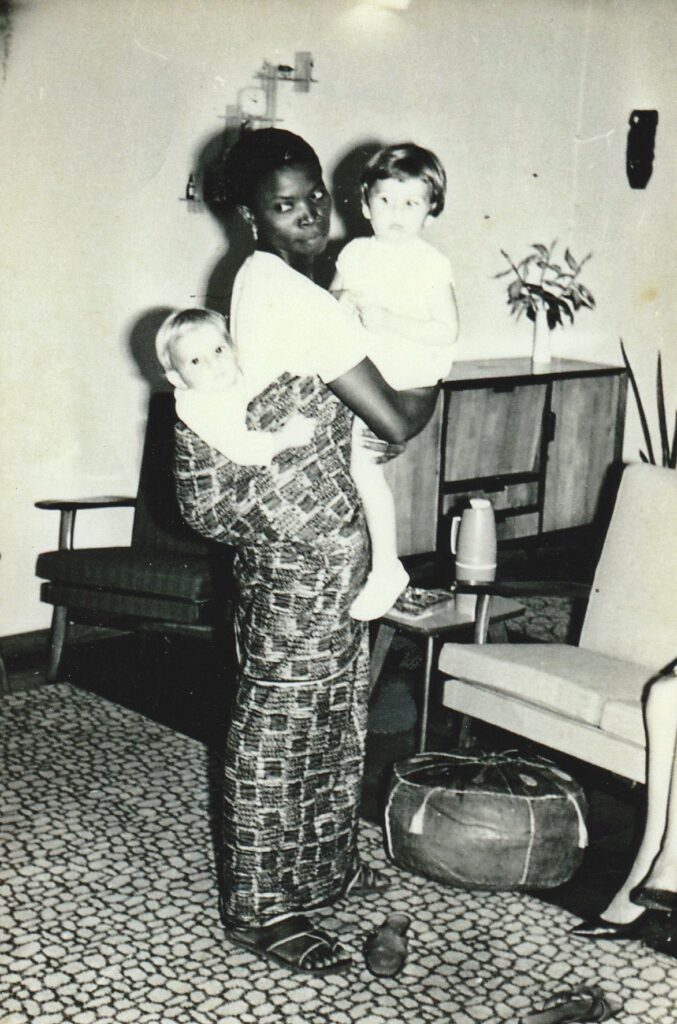

Born in New Zealand, Christina’s first move came at the age of three weeks when her family moved to Fiji. Before landing in the USA as a teenager, she also lived in Sweden, UK, Nigeria, and Australia. After living in three Spanish-speaking countries as an adult, she now resides in Los Angeles. https://christinahoag.com