By Iona McHaney Marcellino

Every April, our mission board used to have a meeting in South Africa. A team from America would volunteer to come and teach the children whatever programme had been used for their Vacation Bible Schools the previous year.

One year the theme was “Route 66 – A Road Trip Across the United States.” It was a pretty glamorous theme. My friends and I were used to road trips across Sub-Saharan Africa. Some of them rode with their families for two or three days to attend these meetings. I was used to road trips in Angola being halted and rearranged due to de-mining fields or washed out log bridges or Marburg outbreaks.

A roadtrip across the US, even an imaginary one, must be just as exciting.

We wore t-shirts, gorged ourselves on American candy, and made key chains designed like little license plates. We listened to the song “Life is a Highway” every day and watched the movie Cars at the end of the week. We practiced a song called “Route 66” with some vague message about finding God along the way. I had no idea what Route 66 was. I didn’t know I was even singing about a real road; the roads in Angola did not have names. But it was fun to sing and it was fun to be a part of something—until I realised I wasn’t a part of it all.

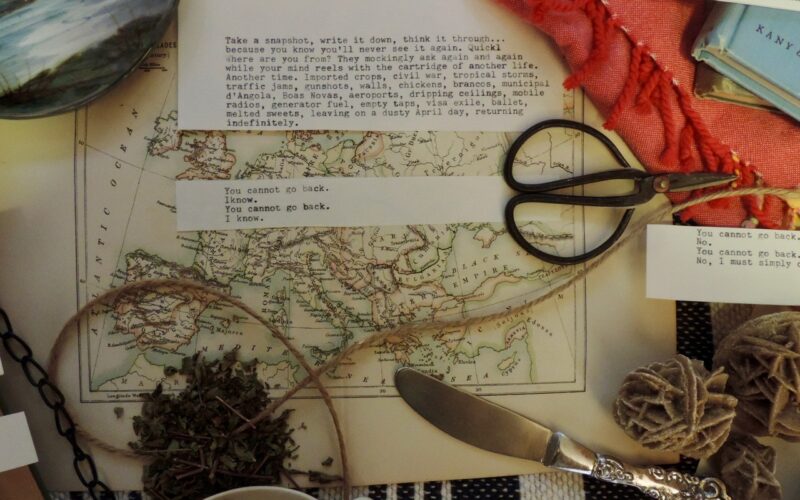

During one afternoon, the American volunteers brought in a massive map of the United States. Each state was outlined, and pictures of the state flowers or landmarks stood out in bright colours. Route 66 (I guess it really does exist) was a solid orange line with a little van to represent our “journey along the highway.”

They handed out stickers to us and said cheerily, “Okay, put the sticker where you were born so we can see which states we are all from!”

I stared at them. I stared at my sticker. I stared at my friends.

My friend next to me stared back—he was born in Botswana. He looked at his brother, who had been born in South Africa. I shot a look at my best friend’s younger brother, who was also born in South Africa. Then I looked around at my other friends: Zimbabwe, Western Europe, Mozambique. I couldn’t see where we were going to put our stickers.

Where I was born is not on the map.

I raised my hand; something had been overlooked and the adults needed to know.

“I’m sorry, but I can’t put my sticker on the map.”

“Oh, sweetie, you can! Tell me where you think you were born and I’ll help you find it on the map!”

I stared some more. The incredulity was astounding. As a ten year old, I didn’t know a lot about the world, I didn’t know where Route 66 went, I didn’t know the references made in Cars, and I didn’t know what a zip code was, but I knew where I was born and I knew the Royal Infirmary of Perth, Scotland, UK, was not going to be found on a map of the United States.

“Where I was born is not on the map,” I said politely.

“Well… where do your grandparents live? Were you born near them? I can help you put the sticker there!”

“No—I wasn’t born in the United States.”

The volunteer stared at me, eyes widening. “But you’re American, sweetie, so you just need to remember where you born—not where you live now!”

“I was born in Perth, Scotland.”

More stares. My friends added their voices.

“I was born in Gaborone!”

“I was born in Johannesburg!”

“I was born in Mozambique!”

Eyes widened even more.

In that moment, I felt sorry for this American volunteer. She had run this whole VBS programme in her home church where all the kids were probably born a few counties apart. She didn’t know that she was being sent to teach the same programme to a bunch of kids who would mess up all her activities on an international scale because of where their parents decided to give birth.

And, yet, there it was. That niggling feeling of shame. Guilt with no cause. A feeling I was aware of and familiar with—because this was not my first encounter with Americans who did not understand me.

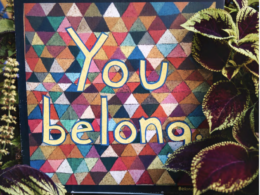

We all felt it. The mis-belonging. The mis-placing of ourselves and the utter inconvenience we caused the volunteers. We didn’t mean to—we were children—but we could see it. We weren’t so much in the way as just extra afterthoughts on a page, no one quite sure what to do with our answers. No one quite sure what to do with us. I’ve encountered this same misplaced guilt and unintentional inconvenience throughout my life as a TCK.

It’s in the long pause when I answer someone’s question, “Where are you from?” I can tell they are taken aback by my response; it’s not what they wanted. Most people want a one-country answer, not a seven-nation saga.

I see it in the frustration of friends and family who are not TCKs and don’t know what it means for me to “not be American” or not feel at home in one place or another.

There is hesitation at every introduction. Do I bore or overwhelm this person with the truth, or do I minimise my life for their comfort?

Often, TCKs minimise because we have to survive. We know that we require community, and to have community we need to be tolerated by other people, and in order to be tolerated we cannot keep overwhelming or correcting other people with our multicultural identities. We simply have to assimilate and be who they expect us to be: American, British, Kenyan, or any other nationality that fits on their map.

Often, TCKs minimise because we have to survive.

And in this assimilation, we lose a lot of ourselves—not always in a drastic, self-effacing way but in a quiet “Oh, this bit of me doesn’t quite fit here” way. Sometimes that “bit” is our second language, sometimes it’s our politics, sometimes it’s our favourite books or hobbies, sometimes it’s all of our childhood memories, sometimes it’s our high school experiences.

It’s difficult to feel like you belong when everyone is sharing their stories of driving to Sonic with their friends after high school and you mention that after school you and your friends ran alongside abandoned train tracks in the Rift Valley, watching out for gunmen. Or that your school trips were to climb Mount Kenya while your university peers went to SeaWorld.

It’s difficult to belong when your peers talk about their favourite shows and ask you what you watched growing up. You respond that you had no electricity so you often watched the lizards running back and forth on your concrete wall.

It is difficult and self-estranging. The conversation is immediately doused and the participants forced to stand about in awkward silence. So, we TCKs minimise our stories. We preface our stories with the disclaimer, “Oh, my life wasn’t that different! I understand life here too!’

I’ll confess, we’re lying through our teeth. But the guilt of lying is somehow more comfortable than the guilt of being an inconvenience, the guilt of not belonging. We alter our stories to make our audience, friends, family, peers, or dates more comfortable and more likely to stick around for the long haul.

We need community and often we’ll do anything to secure it.

Tapering our stories is a skill TCKs learn at a young age; adapting to our environment to maintain acceptance is natural. But what I don’t think is understood by those around us, and what is so keenly felt by the TCK, is the very guilt of simply having a TCK existence. An existence that wasn’t our choice, but one with consequences we feel acutely. An existence that we will have to explain and compensate for over and over and over and over again (and again). An existence that will not be understood, or accounted for, or given space. We are required to give grace repeatedly for those misunderstandings.

Because if we don’t, we’ll be isolated.

Is this guilt just another part of the TCK identity? Is this just another aspect of ourselves that we all need to come to terms with? We carry the responsibility of calibrating our conversations for others. We carry the weight of extending grace when we are misunderstood, mis-remembered, and mis-placed.

In the end, the volunteers put our stickers on a blank piece of paper. We wrote our names and our birthplace beside each sticker and the paper was taped to the edge of the map. We were there, but we were distinctly separate from their world. We were outsiders, our existence denoted on a blank sheet of paper labeled Other, even though Other included the entire world beyond the USA.

It didn’t feel good. We sat there and listened to someone talk about birthplaces and states and I’m sure they tried to tie it to Christ and the Church. I sat and stared at my sticker, an afterthought barely attached to the giant map of the United States.

Looking back, that sticker represents a lot of my relationship with the US. I should belong there. I really should, but I absolutely don’t. The best I can do is find a place on the peripheral edge and cling on for dear life, hoping no one asks too many questions or shakes the map too hard or else my fragile American-ness will fall clean off.

I really did feel sorry for that one volunteer. Even at ten, I had a keen awareness that my friends and I were living a very different sort of life. I knew we had to be gracious to the volunteers, that we had to show an inordinate amount of understanding for our age, because we had access to a concept they didn’t.

You can be American and not born in the USA.

But, because I was a child, I also remember thinking adults really are not that smart and American volunteers don’t know very much about missionary kids except that we don’t have access to American candy. Churches that send teams abroad should be aware of this before they head out to serve missionary kids.

For the sake of the children you’re serving, bring on the sour Skittles and leave your one-nation maps at home.

Iona is a nurse and an avid writer of prose, poetry, and short stories. Born in Scotland and raised in Angola, she now lives in Cambridge, UK with her husband and daughter. Iona enjoys connecting with other TCKs and global nomads to discuss the nuances of this varied, international life.