by Beth Anne Wray

When you are offering hospitality based on fulfilling your own needs, you are not offering true hospitality.

Arriving in Gujarat, India, from boarding school in the foothills of the Himalayas, my siblings and I were always met by my parents at the train station in a town some miles away from home. We were then taken to their friend Isudas’s modest house. There, his wife and daughter ushered us in like family, sat us on the floor as is the custom, and served us hot spiced chai and fresh, crisp pooris (fried bread). This was our joyful welcome after months and months away from our parents. This was the taste of home. This was home. When I returned to Gujarat after forty years, I went to see Isudas’s daughter and told her how much that simple breakfast with her family had meant to me as a child. The next morning, she made me chai and pooris. As we ate, we caught up on each other’s families. That made me feel loved and at home. That was hospitality.

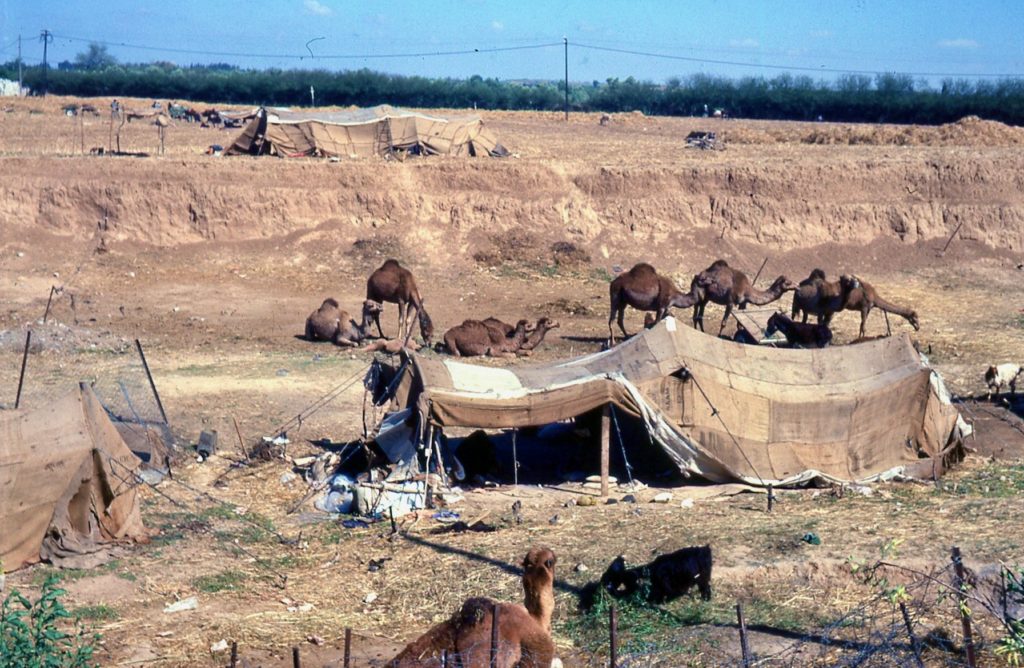

When my parents were transferred to Israel, I felt out of place and missed my birth country of India terribly. But visiting Arab Bedouin tents in the Negev and the Sinai Desert brought back sweet memories of sitting on the ground amongst our Indian friends. It filled me with a profound sense of home when the Bedouins welcomed us—strangers!—into their humble animal-skin tents and sat us down on worn wool carpets beside the sheep and the sleeping babies. We talked with respect about things we shared, like our common ancestor Abraham. We played with their children and their goats and camels and we laughed together. Even without basic amenities like running water, they served us—not cups of chai, but tiny cups of thick, strong Turkish coffee, hot off the fire. Even without a stove or a refrigerator they fed us generously from a huge communal tray—not with pooris, but with lamb and rice and yogurt. It was not India; but it was still love and welcome. It made me feel at home. That was hospitality.

Moving to the Deep South of the United States as a young woman, I discovered a new definition of the word hospitality. There, as in the Arab culture, I was invited quickly and freely into others’ homes, even as a stranger. As in India and Israel, I was generously served food and drink. The gestures were the same. This “Southern hospitality” was indeed beautiful and gracious and friendly to a fault. Yet something was missing.

Even as I perched on comfortable sofas and sipped the ever-present sweet tea in rooms filled with very nice people, I couldn’t really relax. As I dove deeper into the culture, I began to wonder why I could not feel fully at home, fully accepted, fully comfortable, like I had in India and Israel. Was it because I was brand new to the South? Was there something about the customs I didn’t understand? Was I saying or doing the wrong things? I was definitely trying to be equally gracious and polite and friendly, always returning and passing on the hospitality shown to me. Certainly, I had more in common culturally with Southerners than with Indians or Arabs. I reasoned that perhaps after a year, or ten, or twenty, I would come to feel a part of that world; I would lose that feeling of other-ness, of separate-ness, of loneliness. But it never happened for me, even after decades in the South.

How is it that this particular brand of hospitality did not succeed in making me feel at home? Why didn’t I ever feel I truly belonged? That I mattered? That someone wanted to get to know me, the real me? Maybe because that was never the goal. Perhaps, in the South, true hospitality is reserved only for close family and friends. Strangers, even those who have lived there for a long time, remain strangers. Or is it possible I experienced a warped version of hospitality? Were those delicious dinners more about showing off the host’s cooking skills? Was the tea served in expensive vintage glassware in order to display the hostess’s money and taste? Even the stimulating conversation—was it actually intended to prove his or her intelligence?

Since living in India, Israel, and the South, I have traveled to many different countries. Sometimes I have felt warm and accepted like I did as a child; and other experiences have left me with an empty, disconnected feeling. Why is that? Certainly, there are cultural differences and people can be more reserved or more open based on societal norms. But you can always find exceptions to the rule. There are hospitable and inhospitable people in every part of the world.

Here’s what I’ve come to realize: when you are offering hospitality based on fulfilling your own needs, you are not offering true hospitality. When your motives are to present a picture-perfect image of yourself and your home, you are not offering true hospitality. When you use others to fill your space so you don’t have to face yourself in the mirror or face your family, that is not offering true hospitality. When you ask people over because “that’s how it’s done around here,” and you are just fulfilling social obligations, that is not offering true hospitality. When you invite the boss for dinner because you are angling for a raise, that is not offering true hospitality. When you open your home only in the moments when it’s clean and orderly and the kids are behaving and the food is just right, and it’s convenient for you, that is not offering true hospitality.

What, then, is true hospitality? For me, it is reaching out to connect with others at the time when they (not you) need it. Inviting them over when it’s been a rough week and you’re tired, but you know they are more tired. It’s about serving them humbly, and showing respect for their preferences and beliefs. Making a vegan meal even though you’re uncomfortable with that kind of food. Asking the Syrian refugee mom to show you how to cook her food in your kitchen. Giving them the chance to tell their stories. It’s about creating a calm and welcoming space for someone who feels abandoned or rejected or angry or lonely or lost. And creating a space for joy when someone is happy and they want to share it. It’s putting aside your own daily burdens and worries and showing others that they have a home with you. True hospitality makes others feel like I felt as a child sitting on a rug on the floor surrounded by love.

Beth Anne Wray was born in India to missionary parents and went to boarding school in the foothills of the Himalayas. She found herself in Israel when her parents were transferred to Bethlehem, and attended an international high school in Jerusalem. Years later, she married her childhood sweetheart from kindergarten in India.

Travel photos from trips with her husband are posted publicly on Instagram – https://www.instagram.com/gabawray/