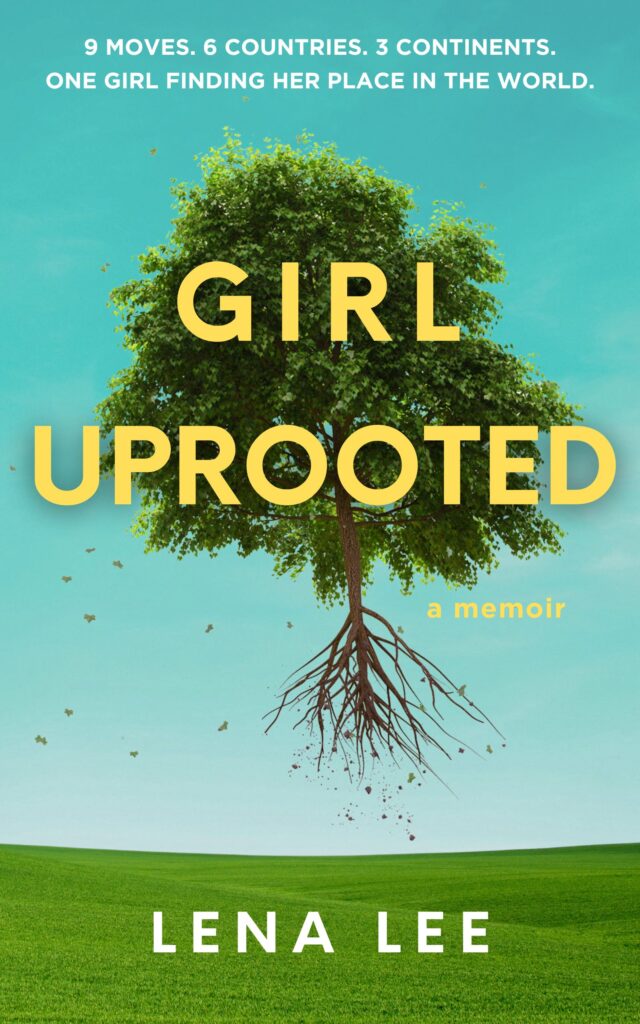

by Lena Lee

The daughter of a diplomat, Lena Lee was born in South Korea but grew up moving countries every three years, her world swinging between East and West. After struggling for many years with her mental health, she recently wrote a deeply personal memoir called Girl Uprooted about her search for a sense of identity and belonging. Below are a few excerpts from various chapters of her life/book.

New Jersey, US, 2002 (age 11)

I rarely experienced overt in-your-face racism, though occasionally kids pulled back their eyes, called me a “chink” or shouted “Ni hao ma” at me. Mostly I ignored it, though sometimes I’d give them the middle finger.

Some kids asked me where I was from. When I said Korea, they wanted to know if it was North or South. I’ve even been asked East or West.

“Do you speak Chinese there?”

“Are you related to Seung Lee [a classmate]?” I couldn’t believe how ignorant they were.

“I heard you guys eat dogs.”

I hated this one. “Eww, no!” I’d say, but I knew it was true. The older generation did eat bosintang, which literally translates to a soup to restore health. I never had it, but my grandpa once took my brother for a meal without telling him what it was. My brother, only a toddler then, complained the soup smelt like his pet dog in Rwanda.

I was terribly self-conscious about Korean food. At home, we would share boiling hot stews called jjigae and various banchan side dishes. The whole house stank when my mom cooked fish, pan-fried and served whole in the middle of the table to share. Using his chopsticks, my dad would adroitly work through the scaly body until only the skeleton was left. He would then gently press around the eyeball until the glazy marble thing popped out. Then the skeleton was flipped so the other eyeball could be extracted. I wished we could eat chicken and potatoes, or at least filleted fish, like “normal” white people. When we moved to Paris years later, I saw that the French too served their fish with eyes. It wasn’t just the uncivilized, barbaric Asians, I thought. As if that made it more acceptable.

Seoul, Korea, 2005 (age 14)

On the first day of school, the teacher introduced me as the new kid from America and everyone clamored for me to speak in English. Looking around sheepishly in my new hand-me-down uniforms, I relented and gave a quick introduction. The classroom stirred; a few kids imitated my pronunciation. “Say something else,” they shouted. News spread down the hall and students came to catch a glimpse of this new girl during breaks. I had no idea speaking English would be such a big deal. I didn’t want to look like I was showing off, so made sure to pronounce the loanwords the Korean way, like “hem-buh-guh” and “cum-pyoo-tuh.”

Even though I started school knowing I would only be there for one semester, I was keen to make new friends. To my relief, the girls—it was a girls’ school—were welcoming and invited me to lunch. Everything about me seemed to fascinate them, even the way I tied my hair into a messy bun at the top of my head—like a topknot, they said. They affectionately called me “butthole panties” because I wore thongs. They giggled when I made some mistakes in Korean, like when I tried to say, “shut my eyes,” the literal translation sounded like I had door handles on my eyes. Or when I said, “make my bed,” it was as if I was manufacturing a bed.

To me, everything and everyone seemed just so “Korean”—in a bad way. Everyone looked the same, straight black hair with bangs. They dressed the same, in the school uniform with a pair of Converse. I couldn’t get over how stereotypically Korean my classmates were. They posed with the peace sign in photos. They held hands and linked arms when walking down corridors. (I learned this kind of intimate, non-sexual touching between friends is called “skinship”—the word itself is Konglish, a fusion of English and Korean words, which Koreans are often surprised to learn are not proper English words.) They were obsessed with the boy band Dong Bang Shin Ki, literally the “Rising Gods of the East,” who to me looked like a group of five effeminate guys. In three years of being surrounded by white people, I had turned into a “banana”: yellow on the outside but white on the inside. It would take many years to undo the damage from such internalized racism acquired during my most formative years.

Paris, France, 2005 (age 17)

After a summer of intensive French lessons, I started the International Baccalaureate, a two-year diploma program. I was being “held back” in a sense as I would have graduated in a semester in Korea, but it was an opportunity to start afresh, both academically and socially, to learn a new language and experience a new country and continent.

So much for the fresh start, I was late on my first day. Well, I had arrived at the school an hour and a half early and decided to wait at a nearby café. Sitting by the window, I watched the throngs of mostly white teenagers hanging out on the sidewalk, some coolly leaning against the railing. I examined them closely. They greeted each other with kisses on the cheek, once on the right, once on the left, holding their cigarettes out of the way. It looked like they were catching up on their summer vacations. I contemplated my outfit—a yellow round neck sweater from Zara, dark skinny jeans and a pair of leather flats, all of which I’d bought that summer—and tried to assess whether I had dressed appropriately.

As 3 p.m. approached, the kids continued to chatter away, the boys playfully jostling each other. I decided to join them outside, but as I rose, all the blood in my body rushed to my head, my knees almost buckling. It felt like everyone was staring at me. I finally mustered the courage to tap a cigarette-wielding kid on the shoulder and ask why everyone was still hanging around. It turned out I was waiting with the wrong group of people. These were the terminale, or seniors. I should have been with the premières who were already in the amphithéâtre, in another building on the other side of the street.

“There you are, Lena!” Ms. Burchill hollered in her deep, husky voice when I opened the door and peeped in. Everyone turned around to inspect the latecomer.

“Hi, sorry!” I said, out of breath. I found an empty seat at the back and scanned the room. There were nearly fifty of us, a mix of ethnicities. I could see a handful of Koreans who unsurprisingly sat together. I knew I was not the only new kid, but I still hated being a new kid. I didn’t know if I could do this yet again. Paris was my opportunity to “reinvent” myself, which I desperately wanted to do after Korea, but I no longer knew who I was or even wanted to be.

I hoped someone would talk to me. One girl turned around and asked if I had a pair of scissors. Other than that, no one spoke to me that day. It seemed first days got harder each time.

Paris was my opportunity to “reinvent” myself, which I desperately wanted to do after Korea, but I no longer knew who I was or even wanted to be.

Oxford, England, 2010 (age 19)

During freshers’ week, which is British speak for college orientation, everyone asked each other what school they went to, what GCSEs and A-levels they took and compared how many A’s they got. It was all gibberish to me. “What’s a GCSE?” I’d ask, interrupting the conversation and exposing my foreigner status. Here I was, an Asian girl with an American accent saying she’d come from a bilingual high school in Paris. (“Asian,” I would learn, is used more commonly in the UK to describe South Asians than East Asians.) Even more confusingly, in between terms, I would go “home” to Norway where my dad was now the ambassador. People couldn’t quite place me, and I felt like an outsider.

There were surprisingly many words and phrases that confused me even, or especially, during casual conversations. When someone was fit, it meant they were sexy, not athletic. Pissed meant drunk, not angry. Brits were chuffed, rather than pleased; knackered, rather than tired. Underwear were pants; pants were trousers. (Never say you don’t wear pants!) They popped to the loo. They went to the cinema to watch a film. Fancy a cuppa? meant “Would you like a cup of tea?” When it came to food, it was pudding for dessert and supper for dinner. Chips were french fries; crisps were potato chips. Then the curse words: blimey, bollocks, bloody, bugger.

It was also the British manner of speech. On the one hand, nothing was ever good; it was “not bad.” On the other hand, mundane things were suddenly brilliant, splendid and marvelous!

London, England, 2023 (age 32)

Writing my story has been one of the most challenging things I’ve ever had to do. Well, I didn’t have to do it, but I’m glad I did. Because as difficult as it was to relive parts of my past, the act of writing has helped me make sense of it. It has forced me to sit down and disentangle the big mess that was my thoughts, feelings and memories and arrange them into words, sentences and paragraphs. In the process, I’ve had to return to times I desperately wished to move on from, but writing and rewriting about these experiences has strangely given me a healthy sense of detachment from my own past, almost as if it’s someone else’s life I’m talking about. I can’t quite describe it, but it has been healing.

Lena Lee is the author of Girl Uprooted, a memoir about her global upbringing and search for a sense of identity and belonging. As a third culture kid, she has lived in Seoul, Paris, Oslo, Kuala Lumpur and New Jersey. After studying Human Sciences at Oxford University, Lena has been living in London, a place she now calls home(ish). Connect with Lena on Instagram @thelenalee.

LINKS TO PURCHASE

Amazon: https://mybook.to/girluprooted

Barnes & Noble: https://www.barnesandnoble.com/s/girl%20uprooted

Waterstones: https://www.waterstones.com/book/girl-uprooted/lena-lee/9781739417109