By Lisa P. Harrill

It was the summer of 1991 at the Wheaton College Science station in the Black Hills of South Dakota, U.S. As a music major, I decided it would be best for my non-scientific brain to tackle all eight science requirements for graduation in an eight-week, immersive environment. Astronomy was fascinating: tracking the stars, planets, galaxies, and constellations in skies unspoiled by urban sprawl. Environmental Chemistry was simple enough to understand, as we hand-collected water samples from the streams and viewed them under a microscope. But there was nothing like Dr. Jeffrey Greenberg’s Geology class. We hiked, went digging, and collected, learning kinesthetically by preparing a rock and mineral collection. I saved some of the collection specimens and brought them home after graduation. One safe-guarded piece is what I call the “Conglomerate.”

The geological world (and the Oxford Dictionary) defines a conglomerate as a “sedimentary rock that is composed of a substantial fraction of rounded to subangular gravel-sized clasts. A conglomerate typically contains a matrix of finer-grained sediments such as sand, silt or clay, which fills the interstices between the clasts.” I stared at the accompanying photo for a time and then the gears of my brain went into overdrive. The word interstices jumped out at me and brought to my mind the 1996 “Ruth Van Reken Third Culture Model.” The middle sphere of this model is entitled “The Interstitial ‘Third Culture’ – shared commonalities of those sharing an internationally mobile lifestyle.” Although some now consider the context of the model to have a few flaws, this description of the Third Culture is still helpful for TCKs to consider.

This is what hit me like a ton of bricks (pun intended): the conglomerate is a precise metaphor for third culture kids. We are a conglomeration, composed of previously experienced cultures. The exact cultural proportion is unique to the individual. This can be influenced by such variables as developmental level, culture(s) of family of origin, personal and environmental mobility, etc. Consequently, no two TCK conglomerates on the planet look exactly the same. The proportion of their elements depends on a wide variety of environmental variables such as age, experiences, and surrounding cultural atmospheres.

If you look at a conglomerate, each smaller rock within it is its own geological sample. If removed from the conglomerate, each could be geologically classified, such as shale, coal, or jasper, depending on the sample. If you know a TCK, you can often see the traces of the unique cultures that have been incorporated in their worldview, dress, speech, etc.

Even more interesting is the “matrix of finer-grained sediments such as sand, silt or clay, which fills the interstices between the clasts” (from “conglomerate” on Wikipedia). Interestingly enough, the term “interstitial” is also used in biology, referring to the space between cells that can be made up of fluid and proteins.

And in architecture, an interstitial space refers to “an intermediate space located between regular-use floors, commonly located in hospitals and laboratory-type buildings to allow space for the mechanical systems of the building” (from “intertitial space” on Wikipedia). As you look at definitions of conglomerate and interstitial, one term that keeps surfacing is between. And isn’t that the case for TCK—that we are always “between?” As an ATCK, it is for me.

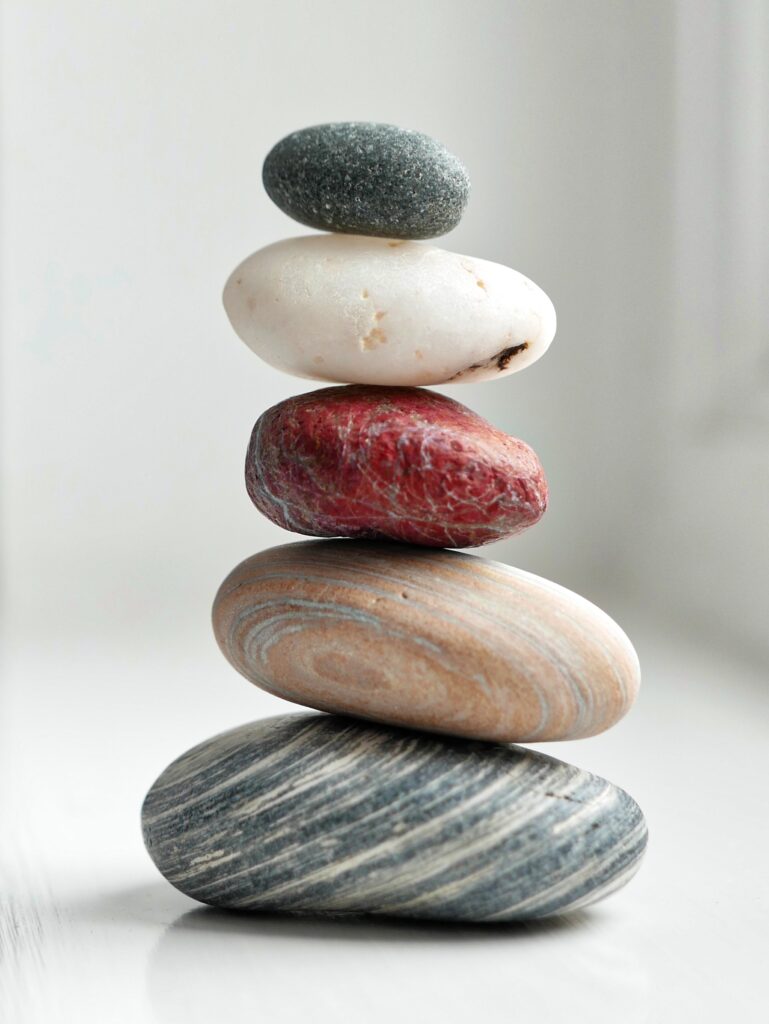

My parents brought me as an infant from Hawaii (basalt or in Hawaiian, “pāhoehoe”) to Panama (alumina and silica) and raised me in the U.S. community of the Panama Canal Zone (Miocene volcanic and sedimentary rocks). These fortified my identity until leaving home for university in Chicago, IL (limestone and dolomite), U.S. Upon college graduation I came home to Panama (red clay and sand) in transition for graduate school. After graduation, I spent two years training in Colorado (granite), and then returned to a new, post-U.S. canal Panamá (cement: calcium, silicon, aluminum, iron). Although my husband and children have the privilege of passports in both locations, I only hold legal residency in the country where I have lived for forty-five years. For this reason, I would like to think of myself as a conglomerate consisting of pahoehoe, alumina/silica, Miocene volcanic/sedimentary rocks, limestone/dolomite, red clay/sand, granite, and cement. The size of each of these rocks depends on my age when I lived there, length of stay, the integration of surrounding cultures permitted by my parents, and more.

What is worth further consideration is that although around the world, conglomerates are made up of different rocks, these rocks are all held in place by the same material, which the Oxford Dictionary describes as “a matrix of finer-grained sediments such as sand, silt or clay, which fills the interstices between the clasts.” This is what they have in common.

TCKs—although made up of a collection of varied amounts of many cultures—all have one thing in common: the interstitial Third Culture. This Third Culture is an elusive concept that escapes the most astute anthropologists and sociologists. How does one define “Third Culture?”

Many TCKs know the progression of the definition of the term third culture kid. Drs. John and Ruth Hill Useem developed the rudimentary definition during their second family move to India in 1957, saying that TCKs are “the children who accompany their parents into another society.” David C. Pollock extended the definition in 1989 with the following: “A TCK is a person who has spent a significant part of his or her developmental years outside the parents’ culture. The TCK frequently builds relationships to all of the cultures, while not having full ownership in any. Although elements from each culture may be assimilated into the TCKs life experience, the sense of belonging is [often] in relationship to others of similar background” (from Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds). And Pollock, Van Reken and Michael V. Pollock adjusted the definition further in the third edition of that book in 2017 with “A traditional Third Culture Kid (TCK) is a person who spends a significant part of his or her first eighteen years of life accompanying parent(s) into a country or countries that are different from at least one parent’s passport country(ies) due to parent’s choice of work or advanced training.”

But again, how does one define “Third Culture?”

The cultural influences surrounding the TCK can be defined, some more clearly than others. A TCK seminar put on in 2001 by the Association of Christian Schools International (ASCI) delineated a variety of TCK sub-cultures. The “passport culture” can be described. The “host culture” can be explained. The “sponsoring community culture,” and “caregiver culture” can be noted. Less clearly defined but still detectable are the “educational community culture,” “expatriate community culture,” and even “other dominant subculture community cultures.” As you can see, defining what goes into the Third Culture requires much deliberation.

Reflecting on our conglomerate analogy, perhaps the answer is too simple. Conglomerates (TCKs) consist of several smaller, self-contained rocks (cultures) of various sizes, connected interstitially by sand, silt or clay (The Third Culture). Perhaps that definition is less “cemented” than what anthropologists, sociologists, or even TCKs and those that care for them would prefer, but I offer it here as another analogy that might contribute to the ongoing discussion.

Lisa P. Harrill, an ATCK, has served as the Children’s Pastor at her home church, Crossroads Bible Church (CBC), an English-speaking, international, non-denominational church in the canal area of Panamá City, Panamá, for ten years. She and her ATCK husband David have also served at Crossroads Christian Academy, a ministry of CBC, for twenty-four years. They are privileged to have raised another generation of TCKs in Panamá, JJ and Eva, now in university in the U.S.