There are few things TCKs love more than getting together and sharing our stories.

Often, our stories highlight the adventures, the great times, and the wonderful experiences we had. Other times, though, the stories wander down a dark path, recounting the pain, loss, even abuse we experienced and the resulting ripple effect.

With all the stories we share amongst ourselves, people often ask, “So, was growing up a TCK a good experience or a bad one?” Which was it for you?

The truth be told . . . it was both, and.

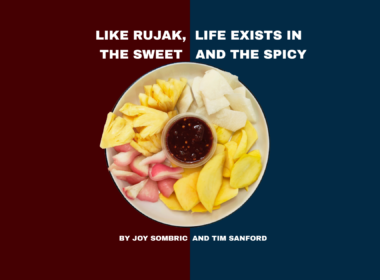

One of my (Joy) favorite treats growing up in Indonesia was rujak. Westerners are less familiar with the juxtaposition of sweet and spicy. To make rujak, take a look around and work with what you have. You may sneak over a fence into a field, raid your mom’s pantry, or ask a neighbor for ingredients. The result is a combination of crisp and crunchy fruits and veggies, dipped in a sauce of brown sugar, fresh chiles, tangy tamarind, and peanuts. The perfection is in the spicy and sweet of it all, in the balance of the two. Too much of one, and you can’t even touch it to your lips; too much of the other, and you’ll feel sick.

Regardless of how many languages you speak, the hardest word to truly comprehend is the word and (English), y (Spanish), dan (Indonesian). Why? Because we tend to think in terms of either/or. It’s black or white. It’s one or the other. You had a good childhood or a bad one.

There’s a growing body of evidence about TCKs and the trajectory of our lives over the decades. Research confirms what we already instinctively know: TCKs have more Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) than the typical “home-grown kid.” Our globetrotting lifestyles can come with consequences, making us more vulnerable. The moves, lack of continuity in education and relationships, separation from parents and siblings, and language barriers can set us up for hard times, neglect, abuse, and falling through the cracks.

But wait, there’s more bad news! High ACEs scores are linked to serious issues such as heart disease, mental health problems, obesity, difficulty connecting with others, and shorter lifespans, to name a few.

For some of us, our parents and sending organizations frown upon talking about—even deny the reality of— the hard things. But we’re designed to pay attention to pain. Why? So we can “fix” it and heal. Our primal survival instinct cannot neglect or ignore pain; rather, we’re drawn to it so we can contain it, heal, and develop scar tissue. This is the stuff of resilience.

The crazy thing is, without realizing it, the pain can cause us to become myopic. All we see is the pain and damage in our story. It’s like staring into the campfire at night; we know it’s messing up our night vision, but still, we stare anyway.

Only acknowledging the bad, painful, or abusive events leaves us with an incomplete (not honest) narrative. Likewise, verbalizing only good, great, and wonderful experiences leaves us, again, with an incomplete (and not honest) narrative. We need the honesty of the and if we want our lives to be balanced and healthy.

The very contrast that comes with the and is what makes each of our stories unique. We’ve experienced some really high highs, and we’ve also lived through some extremely low lows. It’s that spectrum of highs and lows, pain and joy, sweet and spicy that makes you uniquely you—and your story worth sharing. We’re deeper and richer because of it all.

There’s no need to discount any part of your story. You don’t have to pretend everything was “perfect” and nothing bad happened; at the same time, don’t think it was all bad and devoid of anything good either. The word and occupies an important place in your narrative; it gives your story validation and honor.

Think back to the rujak. Its perfection lies in how it’s sweet and spicy, both together. That’s exactly what makes our stories genuine and full of color. It’s the both, and.

But maybe you can’t find a place where the and fits into your narrative. OK, let’s begin here. Ask a friend, a mentor, or a therapist to help you. If you haven’t yet, address whatever pain, trauma, or abuse you lived through so you can heal. From there, slowly work on adding the word and appropriately into your narrative.

For me (Tim), I’ve come to the place where I can see my story as spicy– traumatic things no child deserves to endure– and sweet, the exciting, adventurous things few kids my age got to experience plus things I wouldn’t trade for the world. I’ve come to embrace the word and. It lets me share more than just the adverse experiences embedded in my narrative. My philosophical glass is “half full” and “half empty,” both. That’s reality. That’s my story, complete and honest.

Our encouragement as fellow TCKs is to live the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth. Admit to (and deal with) the bad, adverse, abusive, and hold on to (and enjoy) the good, wonderful, and satisfying.

Like when I (Joy) make rujak, be sure to integrate the joys you’ve experienced while honoring the pain of your upbringing. Life exists in the sweet and the spicy.

BIO: Joy Sombric is an MK from Indonesia, Licensed Clinical Social Worker and therapist with 20 years of experience. She offers seminars and workshops about the unique needs of TCKs.

BIO: Tim Sanford is a Licensed Professional Counselor with 36 years’ experience and an MK from Ecuador. He is the author of “I Have to be Perfect And Other Parsonage Heresies” and other books.