By Casey Eugene Bales

From age three to age nine, I was raised in Tokyo, a city with neon-lit streets, crowded sidewalks, and towering skyscrapers. Walking through this metropolis, especially when underground, made me feel insignificant within the endless waves of people going about their daily business. Despite the mass of people, I couldn’t help but wonder in awe at the regard the Japanese had for others. When I was around eight years old, I remember Mom accidentally leaving her purse at a bus stop in the district of Sangenjaya and then returning hours later to look for it. To her relief—and surprise—the purse was still there with everything inside it. Of course, that was the early nineties and things may be different now. But this Japanese collective behavior had a strong impact on my moral upbringing as it taught me about honesty and doing one’s best not to inconvenience others.

When I left Hawaii and returned to Japan in 1997 at the age of eleven for my mother’s new teaching destination, we moved to a small farming village surrounded by rice fields. I enrolled in a country elementary school for fifth grade. I was considered a kikokushijo (returnee child) and was expected to assimilate back into the Japanese educational system without a hiccup. It was challenging, to say the least.

Located in Niigata prefecture northwest of Tokyo, on Japan’s largest and most populated island of Honshu, Nakajo was a small, rural farming town famous for cultivating koshihikari rice. It’s now known as Tainai City. My walk to and from school was long: one hour there and one hour back. I trudged through several feet of snow, past white blanketed rice fields in winter and grassy green paddies during early summer.

As a family, we were an enigma in Japan. My step-father, Wade, looked like a Japanese national yet could not speak the language. I looked like a foreigner, but I could speak Japanese like a native. Often, in a restaurant, a waiter or waitress would approach Wade only to end up speaking with me. A Japanese man who owned a local restaurant once raised his voice

at Wade when Wade stayed quiet as I spoke for him. I guess the man felt shunned by Wade’s silence. Or maybe he’d just never come across a Japanese-looking man being spoken for by a fluent young (foreigner) child. It was great to be back in Japan, but it was still difficult fitting in with the local kids. They were country boys; I was a gaijin city kid—and I had just come from America. Having small scuffles during recess and cleaning time was common. I grew accustomed to not only verbal but physical abuse as well. After school, boys would throw snowballs spiked with rocks at me and shout, “Go back to America!” Wade understood the challenge I was going through and advised me on handling difficult situations, like when a group of boys tried to ambush me on a quiet backroad. He volunteered to meet me after school and accompany me home on foot or bicycle whenever he thought I might be in trouble. In many ways, as I became Wade’s personal translator, he became like my personal Mr. Miyagi from the 1984 film The Karate Kid—Wade even caught a fly with his chopsticks once.

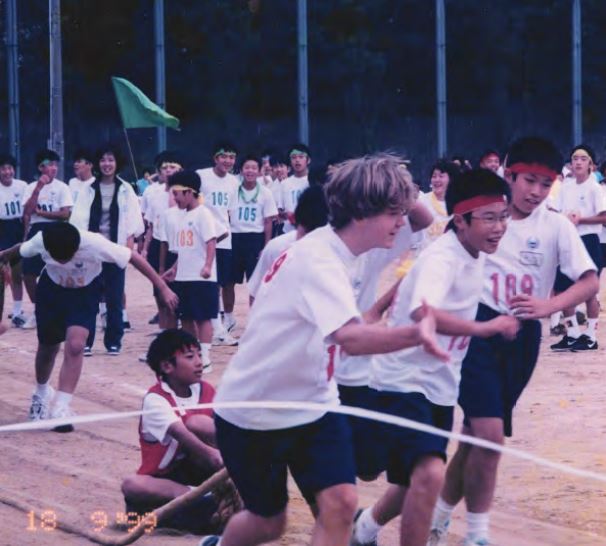

I moved again in 1998 for sixth grade when Mom accepted a teaching position at Kanazawa Institute of Technology, an engineering university. With a fifteenth-century castle overlooking the city and well-preserved Edo-era architecture, Kanazawa is located on the west coast of Japan’s central island of Honshu, along the Sea of Japan. I was much better at making friends here. However, I do remember it wasn’t perfect. As is typical at Japanese schools, students were required to exchange their outdoor shoes for indoor shoes upon entering the building. Each student had their individual shoebox where they would store their footwear. Twice at the end of the school day, I was met with piercing pain when I placed my foot into a shoe filled with thumbtacks. I asked my male friends, and they suspected it might have been some of the girls who didn’t think so well of me and wanted me to quit going to the school. Lucky for me, I bonded with my sixth-grade teacher and became obsessed with playing sports, especially soccer. I developed close friendships with several of my male classmates, with whom I later entered junior high school. It was in junior high school that I remember being ecstatic to win a relay event at the school’s annual undokai (sports day) for my red team. Those same good friends later traveled to Indiana to visit me.

I felt comfortable at Takaodai Junior High School in Kanazawa wearing the required gakuran, a uniform modeled on the uniforms of the European navy. It consisted of long black pants and a jacket with a standing collar. The jacket fastened from top to bottom with golden buttons embossed with the school emblem. Wearing this uniform was a sign of earned maturity and educational promotion all over Japan. It was at this time that I became obsessed with drawing intricate mazes, which probably reflected the path of my life up to that point. I spent hours alone in my room creating passageways that connected, blocked, surprised, and led to various adventures.

During my seventh-grade year at Takanawadai Junior High School, I was elected class president.

There were two factors that led up to this moment. First was when a couple of students and I were called to the front of the class to write kanji (Chinese characters) with the correct stroke order. I was the only one to write them in the correct order even though I was not Japanese. That impressed the teacher and my classmates. Second, it was probably my newfound popularity and blond hair. As young teenagers, we rebelled by doing things naughty young boys typically do, like smoking cigarettes or buying an adult magazine. I knew we were breaking cultural rules of conduct, but risks are only scary when you don’t have friends taking them along with you.

Living in Kanazawa was a time I really felt at home. When asked my nationality back then, I often said I was Japanese, not American. The evening before our flight back home to Indiana from Kanazawa in 2000, I asked Mom to drive me to my junior high school for one last time. The building was dark and empty. It was late at night.

I sat silently in the car, staring at the campus, with only the schoolyard spotlights illuminating the dark buildings. Sadness fell upon me like a coastal fog. These walls housed some of my fondest memories yet; I needed this last goodbye.

The long flight to Indiana the next day felt like heading for outer space. I was flying to a complete unknown. I’d formed a lasting bond, not only with my friends but with Japan and a culture that had become second nature. When people cross borders and get to know one another, it closes the door to hatred forever. I had finally adjusted to my second culture, and I didn’t want to leave.

Casey Bales lives his destiny as a bridge between America and Japan. He spent ten of his formative years being schooled in the Japanese educational system in Japan and later continued his Japanese education in the United States—thereby completing his entire K-12 education as the only non-Japanese in each grade level. Having grown up as a third culture kid (TCK), Casey is continuing his adult cultural journey in Tokyo, Japan, with his wife, Yuki.

*This piece is an excerpt from Casey’s memoir, Invisible Outsider: From battling bullies to building bridges, my life as a Third Culture Kid (Summertime Publishing, 2022).