By Tanya Crossman

Growing up in a business family, attending six schools as we moved four times through three cities on two continents, I didn’t know there was such a thing as a “third culture kid.” I felt the stress of acculturation, re-entry, and the grief of lost relationships without having words for these experiences. I assumed I just didn’t fit in, couldn’t cope with life as well as others did.

I learned the term TCK when I was twenty-three, volunteering with a youth group in China. Two years later I realised this term applied to me, too—this vocabulary explained my struggles. It was a relief to learn I wasn’t just a person who “couldn’t cope,” but that mine were common, understandable reactions shared by many others who experience childhood mobility. In my thirties I became a researcher, collecting the stories and experiences of TCKs from around the world, sharing their perspectives and giving voice to their thoughts.1 Now, at forty, I am delving even deeper into TCK experiences that have not been brought to light before. Together with my colleagues at TCK Training, I am researching the risks of TCK life.

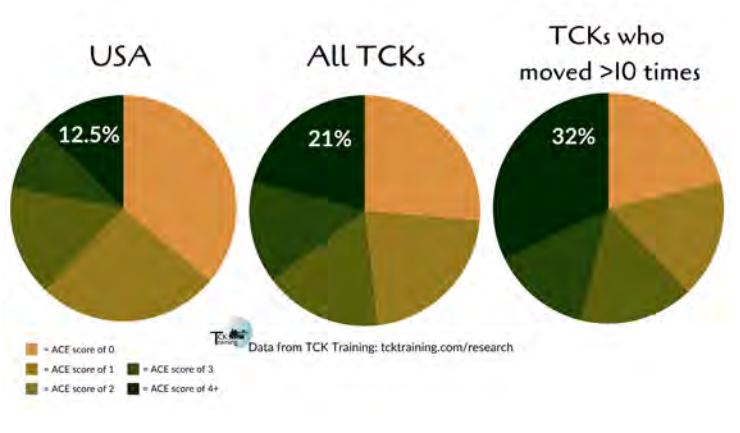

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are a way of understanding the risks of certain childhood experiences and have been researched for decades. When more than three of ten specific experiences are present, the risk of negative physical, psychological, and behavioral health outcomes increases, often dramatically. In a survey of 17,000 Americans, 12.5 percent were at risk. Twenty-one percent of the 1,904 TCKs we surveyed were at the same risk—significantly higher than the rate of Americans.2 One in five TCKs had so many Adverse Childhood Experiences they were considered at high risk of negative outcomes in adulthood. One in three TCKs who experienced extreme mobility were at the same high risk, suggesting that mobility is in itself a risk factor.

There are many reasons we may convince ourselves to downplay the risks of our globally mobile childhoods. Many adult TCKs I’ve interviewed over the past ten years have shared with me the fear of failure they developed: the pressure they feel to live up to high expectations. Some even recognised their pain but did not share it for fear of upsetting their loving parents.

Where prevention and protection were absent, or inadequate, we need restorative care.

Discussing the difficulties we experienced with people who were part of our support network—our parents, caregivers, and friends—can feel very risky. Childhood risks are in the past—why pile additional relational risk on top by addressing past fears now? Engaging with the deeper emotions swirling beneath the shiny exterior often feels like a no-win situation.

There are so many great things that come with international life, but if we fail to discuss the potential risks, we aren’t telling the whole story. “High risk, high reward” still involves high risk. And when there is high risk, there should be high levels of protection and preventive care. Where prevention and protection were absent, or inadequate, we need restorative care.

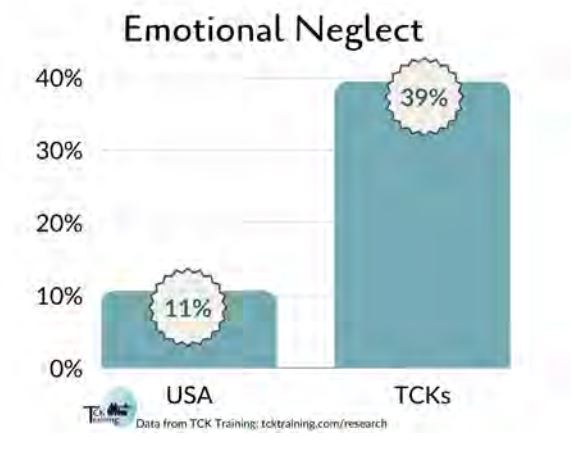

Here is one example from our research. Two out of every five TCKs we surveyed indicated they were emotionally neglected as children.3 We didn’t ask if they were neglected. We asked if as children they felt they were not loved, not special, not important, or that their family was not close and supportive. If you felt that way as a child, you are not alone. Thirty-nine percent of adult TCKs felt the same way as children. Lacking this emotional safety as a child is called emotional neglect, because the deep need we all have for emotional safety was not met.

If you had twenty TCK friends growing up, this research suggests that eight of them were emotionally neglected—that their need for emotional safety was not met. Maybe you were

one of them. That’s a lot of kids in one group. It means that many TCKs may have considered a lack of emotional safety at home normal. “Maybe some people have that, but we shouldn’t expect it.” Maybe we don’t recognise emotional safety when we see it in another home because it’s a foreign concept to us.

If emotional safety is a foreign concept, if we can’t recognise it from our childhoods, how might that affect our romantic relationships as adults? How do we recognise an emotionally safe relationship when dating? How do we know we deserve to be emotionally safe in a relationship if we don’t see emotional safety as normal?

How might it affect our parenting? Even if we understand and want to provide emotional safety to our own kids, learning to do something that wasn’t modelled well in our homes or communities can be difficult.

Many TCKs may have considered a lack of emotional safety at home normal.

This is what happens when we tease out the implications of just one of the Adverse Childhood Experience findings from our research.

Recognising the difficulties of TCK life doesn’t mean we throw out everything. I can acknowledge difficult things, uncomfortable things, and terrible, horrible, no good, very bad things—without letting go of beautiful things, joyful things, and wondrous things. I can live what Lauren Wells describes as “the ampersand life” by embracing the reality of both.4

What I really want you to know is this: you are not alone. Your struggles, then and now, are not because something is wrong with you. Many people have been through what you have been through—even if you haven’t heard those stories yet. The idea of Adverse Childhood Experiences and how they are interrelated with the third culture kid experience may be brand new to you—you are not alone there, either!

I was twenty-five when I realised that the term “third culture kid” applied to me. I was thirty four and the author of a TCK book when I truly internalised that I was a TCK—mostly because Ruth van Reken herself told me to own it, and it’s hard to argue with Aunty Ruth! (She is the co author of Third Culture Kids: Growing Up Among Worlds, Third Edition.)

Maybe you, unlike me, grew up with the term “TCK.” But when did you realise that there were risks associated with TCK life? When were you able to apply those risks to your own experience? When were you able to internalise that knowledge? Maybe it hasn’t happened yet. Maybe it is happening today.

If so let me be your big sister or your Aunty Tanya. Let me say to you: you can take this on board and claim it as your experience. You don’t need anyone else to justify it for you. You know the difficulties you have faced, and you deserve comfort and compassion as you process them. There are those of us who have been there, who understand, and who will stand with you.

You are not alone.

And you don’t have to go through it alone. TCK Training has built a foundation of research showing that others have shared your experiences.5 We have developed tools for adult TCKs to process these experiences.6 I particularly recommend Lauren’s short book, Unstacking Your Grief Tower.

Acknowledging the risks we were exposed to and the difficulties we experienced during childhood can be painful. Integrating the wonderful parts of our international lives with the hard parts—especially when it was all a result of decisions outside our control—can be difficult. Processing brings peace, however, and none of us journey alone.

You are not alone.

References

1Caution and Hope: The Prevalence of Adverse Childhood Experiences in Globally Mobile Third Culture Kids 2022 white paper

2Crossman, Tanya. Misunderstood: The Impact of Growing Up Overseas in the 21st Century.

3Research-Based TCK Care 101

4Wells, Lauren. Unstacking Your Grief Tower: An interactive guide to processing grief as an Adult Third Culture Kid.

5TCK Training Research

6TCK Training services for adult TCKs

Tanya Crossman is the Director of Research and Education Service at TCK Training, and author of Misunderstood: The Impact of Growing Up Overseas in the 21st Century. She grew up in Australia and the US, then lived most of her adult life in China and Cambodia. Tanya began working with TCKs in 2015 and since then has become an author, researcher, and trainer focused on understanding and sharing TCK/ ATCK experiences and advocating for preventive care to improve their long-term outcomes. Learn more at https://tanyacrossman.com or https://www. tcktraining.com.

Instagram: misunderstoodtck Twitter: TanyaTck