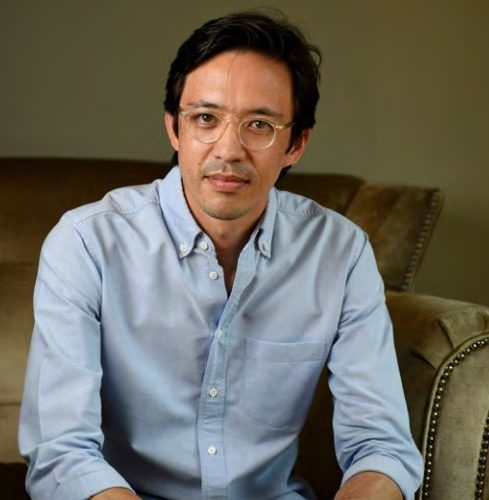

In this issue, we introduce to you writer, journalist, and TCK Ryu Spaeth. Ryu is an editor at New York Magazine. He was born in Hong Kong and grew up in the Philippines and India. In addition to being a TCK, Ryu is also a cross-cultural kid (CCK), as his parents are different nationalities/ethnicities. In this conversation, Ryu describes an experience that many of us have had: first grappling with TCK identity issues upon returning to his passport country for university. In talking about the concept of home, he explains how living in a big city like New York reminds him of other big global cities he’s known. Besides New York Magazine, Ryu’s writing has also appeared in The New York Times, The Nation, and The New Republic. Enjoy getting to know Ryu Spaeth!

Tell us a bit about your experience as a TCK.

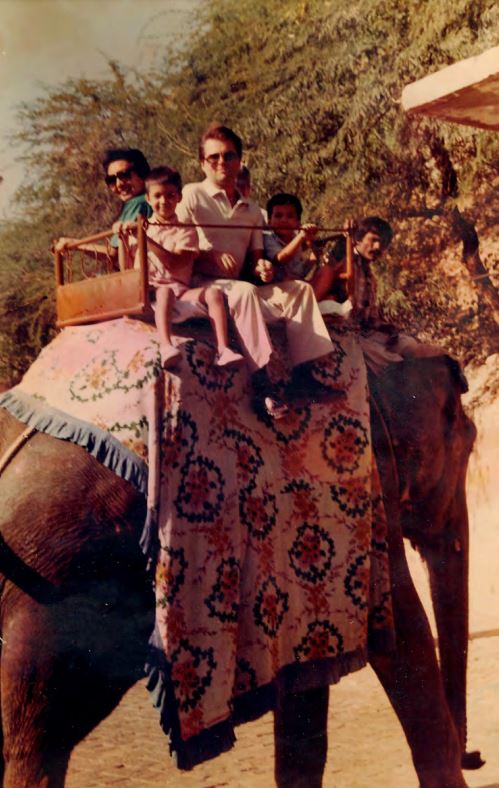

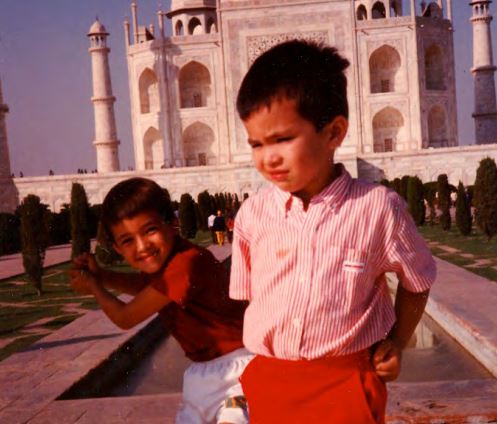

My father is an American from New York who moved to Tokyo in the late 1970s to work at the Yomiuri Shimbun, one of the country’s largest newspapers. He met my mother there. After they married, they moved to Hong Kong, where I was born, then the Philippines, then India, where I graduated from high school in 1999.

When did you learn about the concept of being a TCK? Did it resonate with you?

I think I probably was aware of the concept in high school, but it didn’t really resonate until I moved to America for college, when it became clear that I was neither an American (which was what my passport said) nor an Indian (where I had spent the bulk of my life) nor Japanese (my mother’s country). I felt very much that I was in a no man’s land between places, without a home to call my own, and that feeling stemmed from spending my formative years as a third culture kid.

What early interests guided you into your chosen career?

I’ve always been a reader, and I was always interested in literature and history, two subjects that are of great importance to journalists.

I felt very much that I was in a no man’s land between places.

How have you experienced your background as an asset in your career? In your personal life?

Growing up in India and traveling all over the world have been vital in giving me a perspective that a lot of American journalists don’t have. This was my true education, much more so than anything I learned in university. I think it has probably had a similar impact on my personal life, though it’s also an alienating experience that not a lot of people can relate to. I’ve always felt a bit of an outsider in that respect.

Did your childhood/teen years affect how you think politically, especially in terms of world politics? If so, how?

Absolutely. I feel like I am less susceptible to notions of American exceptionalism, to name one example, and I opposed the Iraq War when I was in college not because I knew anything about geopolitics really, but because of some vague, visceral sense that America was behaving arrogantly and badly. Going to an international school also instilled in me a deep respect for pluralistic diversity and a tolerance for all kinds of people, principles that are unfortunately valued less and less in India these days under [Prime Minister] Modi and the BJP [his party].

What about your background makes you better at your job?

I think being able to see life from other perspectives is important. Knowledge of different cultures also just makes you a more sophisticated person, more worldly; and journalists pride themselves on knowing things, on being people on whom nothing is lost.

What about your background creates hindrances to your work (creative or professional)?

There are vast swathes of American pop culture (particularly television) that are completely unfamiliar to me, which is a hindrance for anyone who wants to write about American life.

Have you struggled with or embraced the idea of “settling down” in one location? What does that look like for you?

I very much wanted to put down roots after college; I didn’t want to roam the earth forever looking for a home. I found that home in New York City, in no small part because it is reminiscent of the places where I grew up. The noise, the bad smells, the chaotic energy remind me of New Delhi, while Chinatown could be a simulation of Hong Kong. And you can find some of the best ramen in the world here, too.

I didn’t want to roam the earth forever looking for a home.

Your writing sounds like you could be an NYC “insider”—do you feel you are? Does it feel like home to you? If not, where is home for you?

I did not feel like an insider for a very long time, but now I suppose I am, in the sense that I occupy a senior position at an elite New York institution. New York is the only place that feels like home, with the exception of Japan, where I spent long summers in my youth and where my relatives live.

This issue’s theme is “Risk.” Tell us about a time you took a big risk (and if it succeeded or flopped).

I suppose the greatest risk I took was becoming a writer. Journalism is a difficult profession even in the best of times, and I could so easily have failed and grown bitter. But if I’ve achieved a modicum of success there’s no guarantee it will last. So, I’ll say the jury is still out on the question of whether I’ve flopped or not—as Montaigne said, “Count no man happy until he’s dead.”